Physically, Gloucestershire can be divided into three main areas; the Forest of Dean and the Wye Valley to the west of a line between the Malvern Hills and the mouth of the River Wye, the Severn Vale running north to south through the centre of the county and the Cotswolds in the east. These landscape attributes affect the climate, such that the Wye Valley is the wettest area in the county, enabling some oceanic liverworts such as Lepidozia cupressina to survive, whilst the Cotswolds are the driest area with Mediterranean species such as Tortella squarrosa (Pleurochaete squarrosa) on the steeper, south-facing slopes. The landscape character is accompanied by differences in land-use which exaggerate the influence of landscape, thus the Forest of Dean and the Wye Valley are heavily wooded and consequently more humid than other areas, the Severn Vale is low-lying with a number of sprawling settlements and extensive pasture, while the Cotswolds are dominated by arable with woodland and grassland along the escarpment and in valleys.

The current and historic land-use within the county, whilst related to the geology, is probably the most important factor currently influencing the distribution of bryophytes. Apart from a few particular areas such as the Wye Valley, the commons of the Cotswold escarpment, the Avon Gorge and nature reserves or other protected areas, most of the county has suffered a significant decline in bryophyte diversity at a local scale. This happened mainly through drainage and conversion of rough ground to arable or improved pasture, exacerbated by massive conversion of land to arable during the World War II. W.R. Price (in Riddelsdell, Headley and Price 1948) notes that even up to the time of writing, the northern end of the Bristol coalfield, around towns such as Yate, Chipping Sodbury and Wickwar contained more heaths than any other area in Gloucestershire. However now, apart from species-poor rough grassland on the remaining commons such as Inglestone and Hawkesbury, these heaths have all but disappeared under improved grassland and housing. Even most nature reserves and designated sites, because they are managed with a focus on other taxa such as vascular plants, birds or butterflies, support low bryophyte diversity, the exceptions being those sites where the management has not changed for tens or hundreds of years.

Marchantia polymorpha subsp. ruderalis, Stroud High Street 2019

It would not be an exaggeration to say that much of Gloucestershire can be considered a bryological desert. For example, most settlements support only the most widespread and abundant species such as Bryum argenteum, Marchantia polymorpha var. ruderalis and Tortula muralis, except where traditional materials such as sandstone or oolite roofing tiles have been used and allowed to weather and support species such as Grimmia laevigata and G. tergestina. Most pasture is now improved to the extent that it supports no bryophytes, apart from one or two more or less ubiquitous species such as Barbula unguiculata and Bryum dichotomum around gateways. Even many woods and hedges support only one or two of the more common species of such habitats, such as Lewinskya affinis (Orthotrichum affine) and Thamnobryum alopecurum and much arable supports few or no species. This is particularly striking in comparison to sites which retain the influence of past habitat management or exploitation, such as the extensive small-scale quarrying of the inferior oolite in the Cotswolds or the carboniferous limestone in the Forest of Dean which has left many abandoned quarries that support some of the rarest bryophytes in the county. It is striking that of the 200 bryophyte species of conservation concern in Gloucestershire, only 61 species (30.5%) occur in habitats which can be described as semi-natural and not entirely anthropogenic.

This and the following account was written by Richard Lansdown, December 2020

Bryophyte recording in Gloucestershire began in the early 19th century with a few records mainly from the Avon Gorge. Subsequently H. Beach produced a list of species that he found in the area around Cheltenham (Knight 1914), but it was only with the establishment of the Moss Exchange Club (MEC) which eventually became the British Bryological Society (BBS) that large numbers of records started to be generated. In the early 1900s, not only were a number of eminent bryologists living in or near enough to Gloucestershire to generate numbers of records, including H.P. Reader, E. Armitage, D.A. Jones, E.J. Elliott and G. Holmes, but the Annual Report of the Moss Exchange Club was published in Stroud. However apart from some remarkable finds away from the “honeypots”, such as the discovery of Rhynchostegium rotundifolium on a lane near Bisley, most records came from The Wye Valley and the Avon Gorge, with fewer records from the Stroud area. This changed when H.H. Knight moved to Cheltenham in 1907. Knight started systematically recording in the county, covering the Cheltenham area by bicycle and parts of the Forest of Dean by train. Knight was president of the BBS from 1933; he published accounts of the mosses (Knight 1914) and the liverworts (Knight 1920) of Gloucestershire. His herbarium collections in NMW and CHM include many significant records made after these publications until his death in 1944.

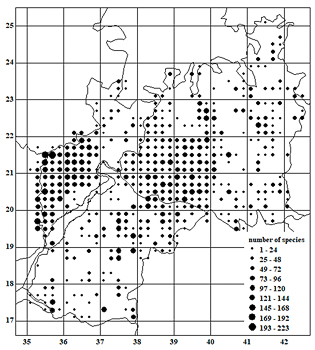

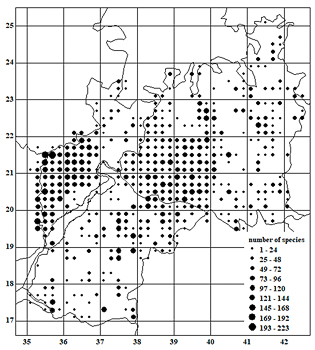

Figure 1: All bryophyte records from January 1990 to October 2020

Until the national atlas project of the 1960s, there was almost no effort made in Great Britain to document the more common species, although Knight appears to have made an effort to retain at least one specimen of each of the species which he recorded in each vice county. Between the 1930s to 1980s, when G.W. Garlick started recording, mainly in the Bristol Coalfield but with a few excursions to the Forest of Dean, few bryophyte records were made. Garlick’s records are the first to be accompanied by six-figure grid references which enable many of his locations to be re-visited. Subsequently, apart from occasional visits to the county by bryologists, mainly to the Symonds Yat area, the next significant set of records was generated by Alan Orange who recorded widely in the Forest of Dean and generated a large number of well localised records of rare or new taxa for the county, as well as enabling useful documentation recording from some poorly known species such as Ptilidium pulcherrimum and Scapania compacta. Another set of useful records was generated by visits of the MEC and subsequently the BBS who recorded within the county in 1925, 1936, 1954, 1968 and 1988, although some of these records need to be treated with caution. Finally, in the 1990s, P. Martin became recorder for the two vice-counties of Gloucestershire, vc 033 and vc 034 which led to the start of systematic documentation of the bryophyte flora (Figure 2). Most of the information available on bryophytes in Gloucestershire comes from a period of only slightly over 100 years and most records have been generated since 2000.

A little over half of the British bryophyte flora has been recorded from Gloucestershire (vcc 33 and 34), representing slightly over one third of liverworts and more than half the moss species (Table 1). However, of these 92, two bryophyte species recorded before 1990 have not been recorded since, in many cases in spite of extensive searches. In contrast, 30 bryophyte species have been added new to the vice county flora since 1990. Some of these were as a consequence of taxonomic changes, some are colonists but a few involve the discovery of established populations which had previously been overlooked. These issues are discussed further under Conservation, below.

Table 1 The number of bryophyte species recorded in Gloucestershire (vcc 33 and 34)

|

total |

pre-1990 |

post-1990 |

pre-1990 only |

post-1990 only |

| Hornworts |

3 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

| Liverworts |

111 |

107 |

86 |

25 |

4 |

| Mosses |

413 |

383 |

349 |

64 |

30 |

|

527 |

493 |

435 |

92 |

34 |

The Cotswolds

The landscape and land-use are both very heavily influenced by the solid geology and it has been said that fewer counties include more geological formations and therefore a greater diversity of rocks and resultant soils than Gloucestershire (L. Richardson in Riddelsdell, Hedley and Price 1948). The solid geology is of particular importance with regard to its influence over whether the overlying soils are predominantly acid, such as the Bristol coalfield and coalfields of the Forest of Dean or calcareous, including the Carboniferous limestone of the Avon Gorge and the Wye valley, the oolitic limestone of the Cotswolds and the sandstones of the Newent and Bromsberrow areas in the north of the county. In contrast, the soils of the Severn Vale are predominantly neutral. Locally there are additional important geological influences, such as calcareous outcrops into predominantly acid areas such as at Wigpool Common and exposures of the acid Harford Sands and the Lias Clays on the Cotswold Escarpment.

The fortunes of the Cotswolds were based on the wool-trade and sheep grazing was the dominant land-use over much of the area. Anecdotal information, paintings and old photographs show that areas of the Cotswolds escarpment which are now wooded were mainly heavily sheep-grazed; this grassland may have supported a wide range of notable taxa, judging by the historical presence of certain species and the character of existing relict grassland. Even though much grassland remains on the Cotswold escarpment and in some of the valleys, diverse bryophyte associations only occur either where slopes are too steep for the more aggressive coarse grasses to establish or in abandoned quarries. This is partly because many areas of the commons are nutrient enriched, but also because even those commons which are managed for conservation are grazed by cattle which do not create the same grassland structure sheep would. East Gloucestershire (vc 33) is dominated by the oolitic limestone massive of the Cotswolds with the highest point on the iconic dome of Cleeve Hill standing above Cheltenham.

The escarpment runs north-east to south-west-west, defining the eastern limits of the Vale of the River Severn in the west and sloping gently eastward toward Oxfordshire. Bryologically, the driving influences in the vice county can be divided into the limestone grassland, woodland and agriculture of the Cotswolds, more varied geology, although again predominantly calcareous, of the escarpment and the more or less level, overwhelmingly neutral clays, agriculture and settlements of the Severn floodplain.

Scapania aspera in an abandoned quarry, Swift’s Hill NR, 2008

Most of the calcareous grassland of the Cotswolds have been severely degraded by over-grazing and agricultural improvement, species-grassland remains only in a few, typically isolated protected sites such as Painswick Beacon, Hornsleasow Roughs and Cleeve Common. Remnant species-rich grassland is typically restricted to the steeper slopes, including former quarries and even the abandoned railway cutting at Harford. The orientation of the slope is a critical factor in the bryophyte flora, with north-facing, colder shaded slopes, some of which retain snow patches for weeks after it has gone from other areas, supporting taller swards with domes of large pleurocarps such as Calliergonella cuspidata, Ctenidium molluscum, Hylocomium splendens, Hypnum lacunosum, Rhytiadelphus squarrosus and R. triquetrus and occasional stands of the southern hepatic mat characterised by patches of Frullania tamarisci, Plagiochila asplenioides and Scapania aspera. In contrast, south-facing, warmer slopes typically have a shorter sward with frequent bare ground and are dominated by members of the Pottiaceae such as Didymodon fallax, Microbryum curvicolle, Microbryum rectum, Weissia brachycarpa var. obliqua and W. sterilis, with a Mediterranean flavour provided by frequent populations of Tortella squarrosa (Pleurochaete squarrosa). This pattern is repeated throughout the intact grassland of the Cotswolds, and the comparison is particularly well represented in the Postlip Valley on Cleeve Common, where the north-facing slope has a well-developed example of the southern hepatic mat both on the scree slopes and in the grassland, while the opposing south-facing slope has abundant Tortella squarrosa and other members of the Pottiaceae, as well as a very large population of Tortella densa at its southernmost British sites.

Frullania tamarisci and Scapania aspera, Hornsleasow Roughs

Cleeve Common is the jewel in the crown of the Cotswold commons, supporting populations of species such as Abietinella abietinum, Aloina rigida, Bryum torquescens, Campylophyllopsis calcarea (Campylophyllum calcareum), Didymodon acutus, Ditrichum flexicaule, Frullania tamarisci, Weissia sterilis and Weissia condensa. It is also remarkable in the context of the Cotswold and East Gloucestershire in the very acidic Harford Sands which are exposed in a few places on the highest parts of the common. Formerly, these sand exposures were exploited by local people and the regular disturbance favoured a range of acidophiles which no longer occur in the county, such as Cephaloziella divaricata, C. stellulifera, Gymnocolea inflata, Isopaches bicrenatus (Lophozia bicrenata), Lophozia excisa, Nardia scalaris, Pogonatum nanum and Racomitrium ericoides. However, the site still supports one of the last UK populations of Atrichum angustatum which has been the subject of conservation work on the common, described below.

Abietinella abietina, Cleeve Common

One of the most remarkable sites in the county was the Pilford Brick Pit near Leckhampton. This is understood to have involved an excavation which eventually resulted in the formation of a lake approximately 600 m2 in surface area dug into clays. It supported the only population of Solenostoma caespiticium that has been recorded in Gloucestershire, as well as a range of species otherwise unknown or rare in the county to the east of the River Severn, including Aulacomnium palustre, Blasia pusilla, Cephaloziella divaricata, Dicranella cerviculata, Gymnocolea inflata, Isopaches bicrenatus (Lophozia bicrenata), Pogonatum urnigerum, Riccardia multifida and Solenostoma gracillimum. There is little detailed information available on the brick works, but it appears that it was no longer operational by 1915 when H.H. Knight visited it, recording many of the notable species. He continued to visit the site often with other bryologists until 1931, but according to a local resident, the pit was filled in and converted to the playing field that currently occupies the site in the mid-twentieth century after two boys drowned and no remnant remains of the habitats which supported the rich bryophyte flora.

The woodland of the Cotswolds is dominated either by beech (Fagus sylvatica) or a combination of ash (Fraxinus excelsior) and pedunculate oak (Quercus robur). Most remaining woodland is on sloping ground on valley sides and the escarpment, although there are scattered copses on the more level uplands of the Cotswolds. Bryologically, these woodlands are unremarkable, with the flora characterised by ubiquitous species such as Amblystegium serpens, Atrichum undulatum, Brachythecium rutabulum, Fissidens taxifolius, Hypnum cupressiforme, Microeurhynchium pumilum (Oxyrrhynchium pumilum), Plagiomnium undulatum, Thamnobryum alopecurum and Thuidium tamariscinum, as well as a range of epiphytes such as Cryphaea heteromalla, Hypnum resupinatum, Lewinskya affinis (Orthotrichum affine), L. striata (O. striatum), Orthotrichum diaphanum, O. pulchellum, O. tenellum, Pulvigera lyellii (O. lyellii), Syntrichia laevipila, S. papillosa, Ulota bruchii, U. crispa, U. phyllantha, Zygodon conoideus and Z. viridissimus. Epiphytic bryophytes are going against the general trends of species loss in the county, and some species may be expanding their range. For example, the epiphytic bryophyte flora which declined with the acidification of tree bark during and after the industrial revolution is recovering, although the recovery does not necessarily involve the same species as were lost. One species which is doing particularly well is Syntrichia papillosa which has been recorded from a total of 25 tetrads since 2000 but was only recorded from three beforehand. Similarly, Cryphaea heteromalla was only recorded from six tetrads before 2000 but 156 since. There are frequent populations of Platygyrium repens in Cirencester Park and along the valley to Sapperton, while there are also a few scattered records of Pylasia polyantha. However, the most significant habitat within the woodland and often around the margins in arable fields and pasture, is the abundance of small oolitic limestone stones which form a major component of the “Cotswold Brash” a stony clay soil which overlies the bedrock throughout the Cotswolds. These stones support a wide range of acrocarpous mosses, including species such as Didymodon luridus, D. sinuosus, Fissidens pusillus, Leptobarbula berica, Seligeria calcarea, S. pusilla, S. donniana and Tortella inflexa, while larger stones, bedrock outcrops and old walls in woodland may also support species such as Anomodon viticulosus, Campylophyllopsis calcarea (Campylophyllum calcareum), Plasteurhynchium striatulum, Porella platyphylla, Rhynchostegiella tenella, and Rhynchostegium murale and stony banks alongside woodland tracks often support a characteristic flora dominated by Encalypta streptocarpa, Fissidens dubius, F. taxifolius and Tortella tortuosa.

Platygyrium repens, on Fraxinus excelsior, Cirencester Park, 2013

Historically, wetlands in the Cotswolds supported wide range of bryophyte species, including notable taxa such as Philonotis calcarean, Sphagnum inundatum and S. denticulatum. However, a long tradition of agricultural improvement has eliminated most of the species-rich wetlands and notable wetland bryophytes in the Cotswolds and these three species appear to be extinct in the vice county. The better quality springheads, flushes and streams at sites such as Bushley Muzzard SSSI and Cockleford Marsh SSSI still support a range of species such as Hygroamblystegium tenax, Aneura pinguis, Brachythecium rivulare, Calliergonella cuspidata, Campylium stellatum, Cratoneuron filicinum, Drepanocladus aduncus, D. sendtneri, Fissidens adianthoides, Palustriella commutata and Pellia endiviifolia with very rare populations of Philonotis fontana. Larger streams then support typical river bryophytes such as Bryachythecium rivulare, Conocephalum conicum, C. salebrosum, Fissidens crassipes, Fontinalis antipyretica and Platyhypnidium riparioides, with occasional populations of Rhynchostegiella tenella and R. teneriffae, as well as some intermediate populations. One remarkable wetland site is the Gloucestershire Wildlife Trust reserve at Severn Springs, near Bourton on the Water which supports an extensive population of Scorpdium cossonii, as well as abundant fruiting Tortella inflexa on stones in the stream in 2011.

Scorpidium cossonii, Severn Springs, 2011

Another significant feature of the Cotswold bryophyte flora is represented by the extensive network of dry stone walls which support a rich flora characterised by species such as Bryum capillare, Didymodon rigidulus, Grimmia pulvinata, Homalothecium sericeum, Hypnum lacunosum, Orthotrichum anomalum, Porella platyphylla, Schistidium crassipilum, Syntrichia montana and Tortula muralis. The best examples support species such as Grimmia orbicularis and Leucodon sciuroides, while one of few known populations of Loeskeobryum brevirostre is mainly on a dry stone wall in Cirencester Park, with a few stands on nearby stones in woodland.

Loeskeobryum brevirostre, Cirencester Park, 2014

Similarly, Rhynchostegium rotundifolium grows on stones in a hedgebank and the base of a tree at one of its two known sites in Britain. Historically, walls would also have supported populations of Antitrichia curtipendula but this species appears to be extinct in the vice county. The flora of walls extends onto the oolite used in construction of buildings, particularly the roofs of houses, churches and even bus stops. These also support a characteristic flora, in particular they support the only known populations of Grimmia tergestina in the vice county.

Leucodon sciuroides with abundant gemmae, Upper Slaughter, 2002

The arable fields of the more level ground in the Cotswolds generally support only a poor bryophyte flora, with a few pleurocarps such as Oxyrrhynchium hians and Kindbergia praelonga growing in the margins, with Barbula unguiculata and a few Bryum species in the field itself. This is partly because of the practice of grazing sheep on the fields after harvest and partly because of the intensification of agriculture. However occasionally a field will be allowed to go fallow for a season or left to grass over before conversion to pasture and these may, for a time, support quite a diverse arable bryophyte flora, including species such as Ephemerum recurvifolium and Weissia squarrosa, while species such as Leptobarbula berica and Tortella inflexa may occur on oolite fragments in the fields.

Fruiting Leptobarbula berica, Hetty Pegler’s Tump, 2005

The Cotswold escarpment

The Cotswold escarpment is typically more species-rich than either the level ground of the Cotswolds or the valleys. This higher species diversity is likely to be due partly to the steeper slopes which made it more difficult to convert habitats to intensive use, partly to the more diverse geology exposed (such as the more acid lias clays) and partly to the diversity of habitats represented including calcareous grassland, woodland and abandoned quarries. Paintings and photographs show that at the height of the wool trade, most of the Cotswold escarpment was converted to open sheep-grazed grassland, but in the 20th century, woodland has recovered apart from in a few areas such as above villages such as Broadway and Snowshill, on Cleeve Cloud and above Leckhampton. Most of the species which occur on the escarpment are also found elsewhere in the Cotswolds but are simply more frequent on the escarpment. However, there are a few species such as Jungermannia atrovirens and Neckera crispa which are clearly very strongly associated with the escarpment, the former on damp tracks in woodland leading to abandoned quarries and the latter on rock faces in very exposed situations in abandoned quarries. In East Gloucestershire, there are a few other species which seem to have a particular association with the escarpment, such as Mnium marginatum which is only known from steep earth banks alongside tracks in woodland on the escarpment, Pohlia lutescens known from one earth bank on the escarpment near Birdlip and Tortula amplexa found once on the margin of a motorcycle course nearby.

Neckera crispa, Cleeve Common, 2004

In contrast to the Cotswolds, the vale of the River Severn is typically very species-poor being overwhelmingly dominated by intensive agriculture and improved pasture, as well as being the location for all of the largest settlements. The only species which are mainly found in the Severn Vale are those of urban habitats such as Bryum argenteum, rough ground, or car parks such as Brachythecium mildeanum and species such as Fissidens fontanus which, in Gloucestershire is only known from the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal. There are also two groups of species associated with the River Severn itself. Bryum gemmiferum, Didymodon tophaceus, Hennediella stanfordensis, Lunularia cruciata and Physcomitrium pyriforme are strongly associated with the unstable clay banks along the River Severn, while a suite of epiphytic bryophytes occur within the inundation zone of the River Severn such as Leskea polycarpa, Orthotrichum sprucei, Scleropodium cespitans, Syntrichia laevipila and the only known population of Myrinia pulvinata in the vice county. Nyholmiella obtusifolia (Orthotrichum obtusifolium) formerly occurred fairly widely on the Cotswolds but in recent years has only been recorded from a single tree beside the River Severn just north of Gloucester.

Myrinia pulvinata near Over

Orthotrichum sprucei near Over

Fissidens fontanus, Gloucester and Sharpness Canal, 2010

Table 2 The number of bryophyte species recorded from East Gloucestershire

|

total |

pre-1990 |

post-1990 |

pre-1990 only |

post-1990 only |

| Hornworts |

1 |

1 |

0 |

3 (100%) |

0 |

| Liverworts |

70 |

61 |

46 |

25 (22.5%) |

4 (3.6%) |

| Mosses |

320 |

291 |

267 |

64 (15.5%) |

30 (7.3) |

|

391 |

353 |

313 |

92 |

34 |

More than a third of the British Bryophyte flora has been recorded in vc 33, but the number of species is very low compared to vc 34 because vc 33 has much more limited geology and habitat diversity. Significantly, more than 50 species have not been recorded since 1990, of which more than a quarter of the liverwort species recorded prior to 1990 have not been recorded since. The most significant losses are acidophile such as Archidium alternifolium, Cephaloziella stellulifera, C. turneri, Gymnocolea inflata, Lophozia excisa, Isopaches bicrenatus (Lophozia bicrenata), Pogonatum nanum, P. urnigerum and Scapania nemorea from sites such as Cleeve Hill and other acid habitats in the Cotswolds. Similarly, it appears likely that Sphagnum species are now extinct in the vice county, having been lost from the spring-lines and flushes of the Cotswold Valleys, as well as acid habitats in the north-east of the vice-county. Two species which also appear to be extinct in the vice county and are likely to be symptomatic of the degradation of grassland and wetland habitats are Climacium dendroides and Rhodobryum roseum. It is possible that either or both of these species could be rediscovered, but extensive searches in all know locations have failed to find them.

Losses from some sites were less significant, for example H.H. Knight recorded Racomitrium canescens, R. ericoides, R. fasciculare and R. lanuginosum imported with ballast used for the railway running east out of Cheltenham, however these species no longer occur on the railway line and it is likely that they only persisted for a relatively short period after introduction. In contrast only a relatively small number of species have been recorded new to the vice county since 1990, most of which are due to taxonomic revisions or improved understanding of their identification or ecology, rather than colonisation such as Dialytrichia saxicola, Didymodon nicholsonii, Flexitrichum flexicaule (Ditrichum flexicaule), Grimmia dissimulata, Grimmia tergestina, Platygyrium repens, Sematophyllum substrumulosum, Tortella bambergeri and Weissia squarrosa.

Bryophytes are poorly served by site protection in Gloucestershire. Where notable taxa occur on protected sites, this is largely by coincidence rather than by design and some of the richest sites for bryophytes are not designated. The vague nature of many records, as well as difficulty in establishing the exact boundary of ownership or management units make it difficult to assess the exact nature of current protection of RDB bryophytes in Gloucestershire. It appears that RDB bryophytes have been recorded from a total of 29 SSSIs, seven Gloucestershire Wildlife Trust Reserves, two RSPB reserves and one Butterfly Conservation reserve. 133 RDB species have been recorded from designated sites and 63 RDB species are still represented on designated sites. Only one RDB species; Tortella squarrosa, is currently known from more than ten designated sites whilst, unsurprisingly all the species known from more than five designated sites are considered Least Concern in the county.

Various mosses fruiting on the experimental wall in March 2017

There has been a well-established programme of bryophytes conservation on Cleeve Common, mainly funded by the Cleeve Common Trust but with some external funding, particularly from Natural England, since 2012. The main focus was initially on attempts to establish a self-sustaining population of Atrichum angustatum (see Lansdown and Phillips 2014, Lansdown et al. 2016) and the experimental re-establishment of a mud-capped wall (see Lansdown and Phillips 2104 and publications due in 2021). The population of Atrichum angustatum can still not be considered entirely secure but is certainly so for the next 5-10 years. The mud-capped wall was extremely successful and toward the end of the experiment it supported thousands of fruiting plants of Ceratodon conicus, among other species.

Ceratodon conicus on the experimental wall

More recently the focus has altered to prioritise development of monitoring protocols for notable species such as Aloina rigida, Frullania dilatata and Tortella densa, as well as an ongoing project to research potential to increase the populations of Abietiella abietina by transplanting soil plugs. Elsewhere in the county there has been work on the conservation of Rhynchostegium rotundifolium (Callaghan 2010, Lansdown 2017) and surveys of a few species, but no consistent or formal programme of conservation work.

Aloina rigida on Cleeve Cloud