-

Making leaves lie flat

-

The leaves of certain mosses have an annoying tendency not to lie flat on a slide, meaning that upper leaf features are often obscured. Falling in this category are the slightly curved leaves of many acrocarps, including Dicranum, Dicranella, Grimmia and Ceratodon. When keying out Didymodon it is important to be able to see whether the cells of the costa in the upper part of the leaf on the ventral (upper) surface are isodiametric or elongate and also, for Didymodon vinealis and related species, to see if there is a translucent groove in the apical part of the leaf. When leaves of such species are stripped off stems and floated under a coverslip, they nearly always orient themselves the ‘wrong’ way up.

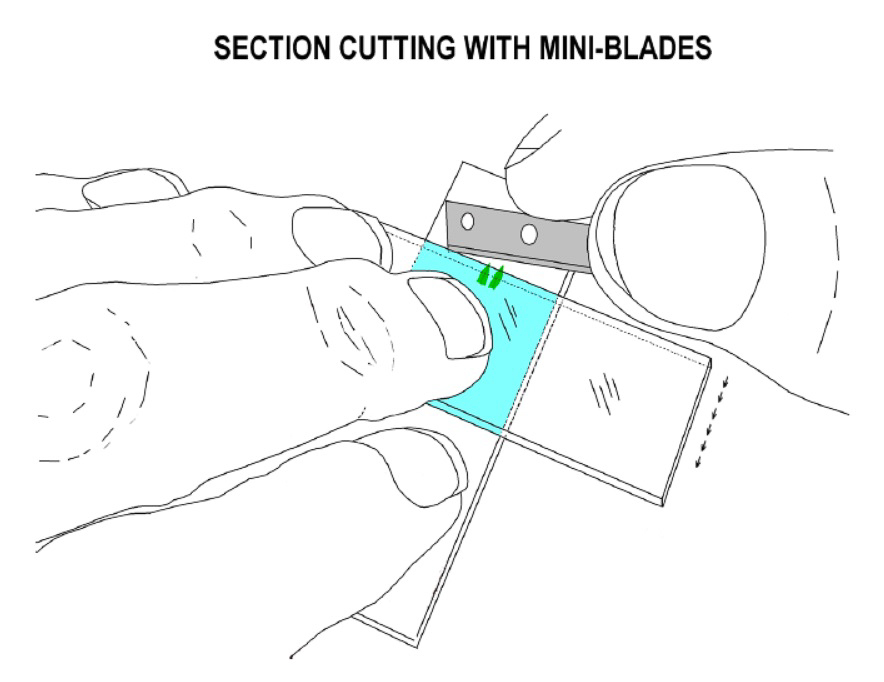

One way to get uppermost part of leaves to lie flat on the slide is to take a whole dry stem, place it on a dry slide under a stereo microscope near a drop of water and, pinning the stem down with a forefinger, cut the uppermost leaves transversely above their mid-point with a razorblade. When the half-leaves are pushed into the droplet, you will find they lie flatter than if they were still attached to their lower portions. In Didymodon, this technique can also be combined with cutting leaf sections, by making the first cut around 4/5 way up leaf tip and then slicing back against the finger to produce a series of very thin nerve and lamina sections.

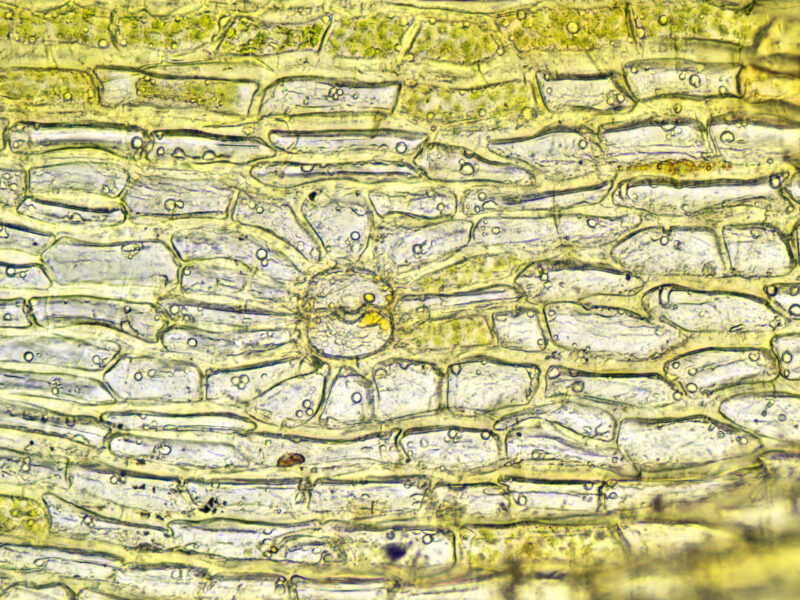

When examining the branch leaves of Sphagnum species, it is often necessary to view or measure pores or hyalocysts visible on the convex outer leaf surface. Unfortunately, because such leaves tend to be very concave, they have a strong tendency to float concave-side up when placed in a drop of water. You can correct this by floating the leaves in a drop of water on a coverslip, placing the slide on the coverslip and then turning it over so that the coverslip is uppermost. This technique can work for Didymodon leaves too.

-

Handling coverslips

-

To avoid getting fingerprints on coverslips, some people keep them on a thin piece of foam; it’s then easy to press finger and thumb into the foam on either side of the coverslip to pick it up. As a further innovation, you could glue a small piece of foam to your stereo microscope stand for this purpose. Read David Wagner’s article about coverslip handling.

Coverslips and slides can be reused many times if kept clean – if they do get dirty, simple apply a few drops of Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) and wipe gently with a tissue or clean lens cloth.

-

Choosing coverslips

-

It is a good idea to have a couple of sizes of coverslip available. It’s surprising what a difference it can make searching for a few leaf sections if you use a small circular coverslip. But a large one is good for examining a number of leaves, especially big ones.

-

Using stains

-

Stain Sphagnum leaves with 1% Methylene Blue, Crystal Violet (or another stain of your choice) to see hyalocyst pores etc. more easily. Staining of the leaves of other species such as Dicranum will also make porose cell walls more visible. Add a tiny amount of stain via a fine dropper (either purchased or made from a recycled eye drops bottle) to a drop of water on a slide and then add a coverslip. Even distribution of the stain under the cover slip can be encouraged by carefully using a tissue to dab the edge of the coverslip to pull liquid across. If you’ve used too much stain, add more water and draw through by using a tissue on the opposite side of the coverslip.

For staining Leucobryum sections or similar small specimens, try placing a drop of stain next to the water containing your sections on the slide. Then drag a small amount of stain into the water using a needle and repeat until it looks dark enough.

Branch leaf, showing pores

-

Removing soil and other debris from rhizoidal gemmae

-

Soil around the rhizoids of small acrocarps such as Bryum, Dicranella and Pohlia often obscures rhizoidal gemmae needed for identification. To remove the soil, half-fill a small sample pot with water, add a small number of stems and soil (it helps if particularly solid lumps are gently broken up with forceps first), screw the lid down firmly and let it soak for at least 10 mins. Then give it several vigorous shakes; if the soil is heavy clay more may be needed. This procedure will detach a lot of soil from the rhizoids and when the plants are then viewed in clean water under a stereo microscope any rhizoidal gemmae should be more obvious. This technique also works quite well to remove encrusted sediment from the leaves of aquatic species such as Rhynchostegiella teneriffae.

Other techniques for removing soil and dirt from specimens on a slide include the use of a very fine paintbrush (place the stem or leaf in water, grasp the base with forceps and gently brush the dirt off). A needle dropper bottle with a very fine nozzle can also be used to wash soil off specimens under a dissecting microscope.

Rhizoidal tubers

-

Using Potassium hydroxide (KOH)

-

If you have access to Potassium hydroxide (KOH), it can be used to clear cell contents and make cell walls easier to see (useful for determining whether cell walls are porose, and for viewing trigones in liverworts).

** Take care when using any chemicals. KOH is a caustic chemical and can cause severe damage such as burning or ulcers, on contact with skin. **

Prepare a 10% solution of KOH. This can be kept in a plastic bottle (an old eye-dropper bottle is ideal) for many months. Place a few leaves in a drop of KOH and leave for 5 minutes, then transfer the leaves to a fresh drop of water, add coverslip and view.